| London Fictions |

|

- Home

-

To 1900

- Daniel Defoe: A Journal of the Plague Year

- Charles Dickens: Great Expectations

- Walter Besant: All Sorts and Conditions of Men

- Amy Levy: Reuben Sachs

- Margaret Harkness: Out of Work

- Margaret Harkness: In Darkest London

- Julia Frankau: A Babe in Bohemia

- George Gissing: The Nether World

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Sign of Four

- George Gissing: New Grub Street

- H.W. Nevinson: Neighbours of Ours

- Arthur Morrison: A Child of the Jago

- William Pett Ridge: Mord Em'ly

- M.P. Shiel: The Yellow Danger

- Arthur Morrison: To London Town

-

1901-1930

- Joseph Conrad: The Secret Agent

- A. Neil Lyons: Arthur's

- Thomas Burke: Limehouse Nights

- Dorothy Richardson: The Tunnel

- Virginia Woolf: Jacob's Room

- Arnold Bennett: Riceyman Steps

- Aldous Huxley: Antic Hay

- Virginia Woolf: Mrs Dalloway

- Christopher Isherwood: All the Conspirators

- Lao She: Mr Ma and Son

- Patrick Hamilton: The Midnight Bell

- Jean Rhys: After Leaving Mr Mackenzie

- A.P. Herbert: The Water Gipsies

-

1931-1960

- Pamela Hansford Johnson: This Bed Thy Centre

- Simon Blumenfeld: Jew Boy

- John Sommerfield: May Day

- James Curtis: The Gilt Kid

- Virginia Woolf: The Years

- Samuel Beckett: Murphy

- Sajjad Zaheer: A Night in London

- John Sommerfield: Trouble in Porter Street

- Patrick Hamilton: Hangover Square

- Graham Greene: The Ministry of Fear

- Louis-Ferdinand Celine: Guignol's Band I & II

- Norman Collins: London Belongs to Me

- Elizabeth Bowen: The Heat of the Day

- George Orwell: Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Rose Macaulay: The World My Wilderness

- Graham Greene: The End of the Affair

- Alexander Baron: Rosie Hogarth

- Jack Lindsay: Rising Tide

- Iris Murdoch: Under the Net

- Samuel Selvon: The Lonely Londoners

- Gerald Kersh: Fowlers End

- Colin MacInnes: City of Spades

- Kevin FitzGerald: Trouble in West Two

- Colin MacInnes: Absolute Beginners

- E.R. Braithwaite: To Sir, with Love

- Lynne Reid Banks: The L-Shaped Room

- Colin MacInnes: Mr Love and Justice

- Colin Wilson: Ritual in the Dark

-

1961-1990

- Colin Wilson: Adrift in Soho

- Terry Taylor: Baron's Court, All Change

- Laura Del-Rivo: The Furnished Room

- Robert Poole: London E1

- Len Deighton: The Ipcress File

- Alexander Baron: The Lowlife

- B.S. Johnson: Albert Angelo

- Waguih Ghali: Beer in the Snooker Club

- Anthony Cronin: The Life of Riley

- Nell Dunn: Poor Cow

- Kamala Markandaya: The Nowhere Man

- Lionel Davidson: The Chelsea Murders

- Penelope Fitzgerald: Offshore

- J.M. O'Neill: Duffy is Dead

- Muriel Spark: A Far Cry from Kensington

- Martin Amis: London Fields

- Hanif Kureishi: The Buddha of Suburbia

- Neil Bartlett: Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall

- Nigel Williams: The Wimbledon Poisoner

-

1991 on

- Peter Ackroyd: The Plato Papers

- Zadie Smith: White Teeth

- Chris Petit: The Hard Shoulder

- Iain Banks: Dead Air

- Monica Ali: Brick Lane

- Naomi Alderman: Disobedience

- Xiaolu Guo: A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers

- Jonathan Kemp: London Triptych

- Martin Amis: Lionel Asbo

- Zadie Smith: NW

- Paula Hawkins: The Girl on the Train

- Natasha Pulley: The Watchmaker of Filigree Street

- Kamila Shamsie: Home Fire

- Michele Roberts: The Walworth Beauty

- Balli Kaur Jaswal: Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows

- Claire North: 84K

- Tony White: The Fountain in the Forest

- Vesna Goldsworthy: Monsieur Ka

- Contact

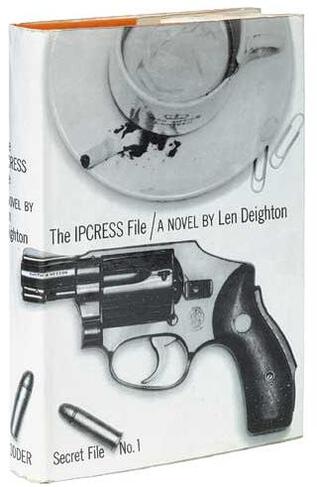

Len Deighton: 'The Ipcress File' - 1962

=Nicolas Tredell=

Like Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ (1899), Len Deighton’s first novel, The Ipcress File, starts in London, moves out of England through a network that follows the contours of global power, and returns finally to the capital. But Deighton’s narrator, an unnamed intelligence agent, begins his tale, not on a cruising yawl in the Thames, but in a Sheraton chair in a government minister’s well-appointed flat overlooking Trafalgar Square. Edward Milward-Oliver’s Len Deighton Companion (1987) suggests ‘Ipcress Man’ as the most appropriate way to refer to this nameless narrator but we will abbreviate it to ‘I.’ in this article, for the sake of concision and also because it sounds the same as the first-person pronoun Deighton’s storyteller uses and, in its similarity to ‘K.’, the initial used to designate Franz Kafka’s protagonist Josef K. in The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926), suggests that I.’s battle with disorientation and misdirection has a Kafkaesque quality, reinscribed in a London-based spy story.

In his tale to the minister, which is supposed to be the basis of the book we are reading, I. retraces an itinerary that takes him across London districts (for example, Whitehall, Fitzrovia, Soho, Shoreditch) and out of England to Beirut, Tokwe Atoll in the Pacific, and, apparently, to a prison in Hungary, then part of the Soviet-dominated Eastern bloc. But times have changed since the 1890s and this is not Conrad’s London, hub of a mighty empire, but post World War Two London, the faltering heart of a fading imperium, where the USA has displaced British power and the flight of Burgess and Maclean to Moscow in 1951 has partly revealed the duplicity within an intelligence service supposedly pledged to protect national integrity.

Len Deighton knew London well; he grew up in Marylebone, went to St Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road and the Royal College of Art, and lived for a while in Soho. But he also knew from experience the filaments that linked London to distant places across the globe. He had worked for a year as an airline steward on BOAC’s long-haul routes to Africa, Japan and Australia, at a time when crews had long stopovers at many places – for example in the Lebanese capital, Beirut, a place of which, according to Deighton, few people had then heard and which provided the setting for one of the key out-of-London settings of the novel. For the other out-of-London setting in Ipcress, Tokwe Atoll, Deighton drew on research and imagination.

Len Deighton knew London well; he grew up in Marylebone, went to St Martin’s School of Art in Charing Cross Road and the Royal College of Art, and lived for a while in Soho. But he also knew from experience the filaments that linked London to distant places across the globe. He had worked for a year as an airline steward on BOAC’s long-haul routes to Africa, Japan and Australia, at a time when crews had long stopovers at many places – for example in the Lebanese capital, Beirut, a place of which, according to Deighton, few people had then heard and which provided the setting for one of the key out-of-London settings of the novel. For the other out-of-London setting in Ipcress, Tokwe Atoll, Deighton drew on research and imagination.

I.’s story starts in December but is not dated to a specific year. At the start of chapter 13, however, he describes a colleague as a man ‘who, had he been a few years younger, would have made a John Osborne hero’. John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger premiered at the Royal Court Theatre in London’s Sloane Square on 8 May 1956, so, by this reference, the earliest starting-date for I.’s narrative is December 1956.

1956 was also the year in which the Clean Air Act was passed, in belated response to London’s Great Smog of 1952, and the London of Ipcress helps to show the need for that Act: it is a grey-on-grey city, yet to experience the polychromatic pyrotechnics of Swinging London and the later refurbishments of monuments and buildings that, like gigantic tooth-descalings, returned them to a simulacrum of their pristine whiteness.

On the day I. is to start his new job, he draws back his curtains after getting up and finds ‘December in London – the soot-covered tree outside was whipping itself into a frenzy’. A month or so afterwards, he walks towards Soho on ‘that sort of January morning that had enough sunshine to point up the dirt without raising the temperature’. This is an anti-lyrical London with sooty trees and soiled sunshine.

Later in the novel, he gazes blankly out one cold April morning ‘across the chimneys, crippled and hump-backed, the shiny sloping roofs, back-yards of burgeoning trees and flowering sheets and shirts’. If the ‘crippled and hump-backed’ chimneys are an idiosyncratic personification in a Dickensian mode, they are too cramped and static to permit of Dickens’s exuberant amplification, while the ‘flowering sheets and shirts’ are ironic in the manner sometimes found in T. S. Eliot’s Waste Land (1922), in which natural processes, in the ‘Unreal City’ of London, shrivel into artificial ones (‘She smooths her hair with automatic hand’).

1956 was also the year in which the Clean Air Act was passed, in belated response to London’s Great Smog of 1952, and the London of Ipcress helps to show the need for that Act: it is a grey-on-grey city, yet to experience the polychromatic pyrotechnics of Swinging London and the later refurbishments of monuments and buildings that, like gigantic tooth-descalings, returned them to a simulacrum of their pristine whiteness.

On the day I. is to start his new job, he draws back his curtains after getting up and finds ‘December in London – the soot-covered tree outside was whipping itself into a frenzy’. A month or so afterwards, he walks towards Soho on ‘that sort of January morning that had enough sunshine to point up the dirt without raising the temperature’. This is an anti-lyrical London with sooty trees and soiled sunshine.

Later in the novel, he gazes blankly out one cold April morning ‘across the chimneys, crippled and hump-backed, the shiny sloping roofs, back-yards of burgeoning trees and flowering sheets and shirts’. If the ‘crippled and hump-backed’ chimneys are an idiosyncratic personification in a Dickensian mode, they are too cramped and static to permit of Dickens’s exuberant amplification, while the ‘flowering sheets and shirts’ are ironic in the manner sometimes found in T. S. Eliot’s Waste Land (1922), in which natural processes, in the ‘Unreal City’ of London, shrivel into artificial ones (‘She smooths her hair with automatic hand’).

I. starts his main narrative with his change of job from Military to Civilian Intelligence, specifically to ‘one of the smallest and most important of the Intelligence units – WOOC(P)’. (We never learn what the letters stand for.) This involves a move from Westminster to Fitzrovia. I. first goes to the War Office – or, as he sometimes more colloquially calls it, the War House – in Whitehall. ‘It had always made me feel a little self-conscious saying “War Office” to cab drivers; at one time I had asked for the pub in Whitehall, or said “I’ll tell you when to stop,” just to avoid having to say it’.

This self-consciousness is one mark of I.’s uneasiness in assuming the upper middle-class manner of most of his colleagues. In the War Office, he takes leave of his former boss, Ross, and moves across London to the premises of his new boss, Dalby. ‘Dalby’s place is in one of those sleazy long streets in Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street’. This sense of an enervated Bohemia, unable to extend beyond its own area, reinforces the sense of decline in the novel.

This self-consciousness is one mark of I.’s uneasiness in assuming the upper middle-class manner of most of his colleagues. In the War Office, he takes leave of his former boss, Ross, and moves across London to the premises of his new boss, Dalby. ‘Dalby’s place is in one of those sleazy long streets in Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street’. This sense of an enervated Bohemia, unable to extend beyond its own area, reinforces the sense of decline in the novel.

The Fitzroy Tavern, Charlotte Street

The Fitzroy Tavern, Charlotte Street

The street turns out to be Charlotte Street, site of the Fitzroy Tavern (where I. once takes a drink), the pub whose name provided the basis for the dubbing of the district as ‘Fitzrovia’ and the launching of a claim to a distinctive identity of its own rather than being simply a failed continuation of Soho. But this term is not used in the novel, as if to rebut any such claim. Charlotte Street has

a new likely-looking office conversion wherein the unwinking blue neon glows even at summer midday, but […] Dalby’s department is next door. His is dirtier than average, with a genteel profusion of well-worn brass work, telling of the existence of ‘The Ex-Officers’ Employment Bureau. Est 1917’; ‘Acme Films Cutting Rooms’; ‘B. Isaacs. Tailor – Theatrical a Specialty’; ‘Dalby Inquiry Bureau – staffed by ex-Scotland Yard detectives’.

In fact WOOC(P) occupies the whole house and these businesses are fronts for its operations.

The boss of WOOC(P) is Dalby (no forename supplied). Dalby’s responsibility is direct to the Cabinet and he is ‘almost as powerful as anyone gets in this business’. He is ‘an elegant languid public school Englishman’, blond-haired and over six feet tall, who has been to a German university in the late 1930s and, unusually in the Intelligence Service, won a DSO and bar in 1941. There is some class-based friction with I., who comes from Burnley and, we infer, attended a grammar school, and who ironically alludes more than once to his lack of a classical education and smokes Gauloises.

I. also differs physically from Dalby, as we learn when I. finds some images in another man’s wallet that he is rifling:

The other three photos were also passport style – full face, profile and three-quarter positions of a dark-haired, round-faced character; deep sunk eyes with bags under horn-rimmed glasses, chin jutting and cleft. On the back of the photos was written ‘5ft 11in; muscular inclined to overweight. No visible scar tissue; hair dark brown, eyes blue’. I looked at the familiar face again. I knew the eyes were blue, even though the photograph was in black and white. I’d seen the face before; most mornings I shaved it.

This combination, in its supposed hero, of Northern provenance, a grammar-school education, an absence of classical learning, baggy eyes, horn-rimmed glasses, a tendency to carry too much weight and a preference for Gauloises helped to make The Ipcress File seem, on its first appearance, like an anti-Bond novel, an abrasive counter to the class-burnished self-assurance of Ian Fleming’s hero. But in his introduction to the Silver Jubilee edition of Ipcress, Deighton denies any intention to make the book ‘a working-class crusade against private school education’ and expresses sympathy with those who had to cope with his chippy protagonist.

a new likely-looking office conversion wherein the unwinking blue neon glows even at summer midday, but […] Dalby’s department is next door. His is dirtier than average, with a genteel profusion of well-worn brass work, telling of the existence of ‘The Ex-Officers’ Employment Bureau. Est 1917’; ‘Acme Films Cutting Rooms’; ‘B. Isaacs. Tailor – Theatrical a Specialty’; ‘Dalby Inquiry Bureau – staffed by ex-Scotland Yard detectives’.

In fact WOOC(P) occupies the whole house and these businesses are fronts for its operations.

The boss of WOOC(P) is Dalby (no forename supplied). Dalby’s responsibility is direct to the Cabinet and he is ‘almost as powerful as anyone gets in this business’. He is ‘an elegant languid public school Englishman’, blond-haired and over six feet tall, who has been to a German university in the late 1930s and, unusually in the Intelligence Service, won a DSO and bar in 1941. There is some class-based friction with I., who comes from Burnley and, we infer, attended a grammar school, and who ironically alludes more than once to his lack of a classical education and smokes Gauloises.

I. also differs physically from Dalby, as we learn when I. finds some images in another man’s wallet that he is rifling:

The other three photos were also passport style – full face, profile and three-quarter positions of a dark-haired, round-faced character; deep sunk eyes with bags under horn-rimmed glasses, chin jutting and cleft. On the back of the photos was written ‘5ft 11in; muscular inclined to overweight. No visible scar tissue; hair dark brown, eyes blue’. I looked at the familiar face again. I knew the eyes were blue, even though the photograph was in black and white. I’d seen the face before; most mornings I shaved it.

This combination, in its supposed hero, of Northern provenance, a grammar-school education, an absence of classical learning, baggy eyes, horn-rimmed glasses, a tendency to carry too much weight and a preference for Gauloises helped to make The Ipcress File seem, on its first appearance, like an anti-Bond novel, an abrasive counter to the class-burnished self-assurance of Ian Fleming’s hero. But in his introduction to the Silver Jubilee edition of Ipcress, Deighton denies any intention to make the book ‘a working-class crusade against private school education’ and expresses sympathy with those who had to cope with his chippy protagonist.

While there are indeed differences between the Bond books and Ipcress, there are also likenesses. Both seem to offer the privileged cognitive access to a concealed world epitomized in the first line of one of the epigraphs to Ipcress, from Shakespeare’s Henry IV 1: ‘And now I will unclasp a secret book’. Deighton’s narrator also converges with Bond in his appreciation of good food. When Dalby treats his new recruit to lunch at Wilton’s, a venerable Jermyn Street restaurant, established in 1742, that exists to this day, I. takes a gourmet’s pleasure in the ‘iced Israeli melon, sweet, tender and cold like the blonde waitress’, the lobster salad and the ‘carefully-made mayonnaise’, even if his more usual lunch venue is ‘the sandwich bar in Charlotte Street, where I played a sort of rugby scrum each lunchtime with only two PhD’s, three physicists and a medical research specialist for company, standing up to toasted bacon sandwich and a cup of stuff that resembles coffee in no aspect but price’.

I.’s first assignment for Dalby is to try to track down a British biochemist, codenamed Raven (all subjects of long-term surveillance have bird names). The Home Office has informed Dalby that Raven has gone missing that morning. He is the eighth top-ranking scientist to disappear in six-and-a-half weeks. Dalby believes that if his unit can find Raven, the Home Secretary will disband his own intelligence department and hand over their files to WOOC(P), an acquisition for which Dalby devoutly wishes. A man codenamed Jay, whom I. has seen with his minder, Housemartin, on covertly shot film, may be masterminding the disappearances. Dalby assigns I. the task of buying back Raven from Jay or whoever else has him and authorises him to offer £18,000, with the option of going up to £23,000.

I. meets Jay and Housemartin in a Soho café called Lederer’s, ‘one of those continental-style coffee-houses where coffee comes in a glass’. Its customers, ‘who mostly think of themselves as clientele, are those smooth-rugged characters with sun-lamp complexions, half a dozen 10in by 8in glossies, an agent and more time than money on their hands’. Jay’s head touches ‘the red flocked wallpaper between the notice that told customers not to expect dairy cream in their pastries and the one that cautioned them against passing betting slips’. Today these details are redolent of a past era in which coffee in a glass was an exotic novelty, actors marketed themselves by means of glossy photographic prints rather than on the web, pastries were often filled with artificial cream, and there were no betting shops.

I. tells Jay he has a financial proposition for him, and Jay and Housemartin take him to what Jay says is a place where they can talk: the narrative offers a montage of I.’s visual impressions and jaundiced thoughts as they walk along Wardour Street:

the three of us trailed out along Wardour Street, Jay in the lead. The lunch hour in central London – the traffic was thick and most of the pedestrians the same. We walked past grim-faced soldiers in photo-shop windows. Stainless-steel orange squeezers and moron-manipulated pin-tables metronoming away the sunny afternoon in long thin slices of boredom. Through wonderlands of wireless entrails from the little edible condensers to gutted radar receivers for thirty-nine and six. On, shuffling past plastic chop suey, big-bellied naked girls and ‘Luncheon Vouchers Accepted’ notices, until we paused before a wide illustrated doorway – ‘Vicki from Montmarte’ [sic] and ‘Striptease in the Snow’ said the freshly-painted signs. ‘Danse de Desir – Non Stop Striptease Revue’ and the little yellow bulbs winked lecherously in the dusty sunlight.

Inside, left alone by Jay and Housemartin, I. decides to explore the premises by himself and finds an upstairs room whose floor is studded with six armour-glass panels, looking like mirrors from below, for covert observation of the gaming room beneath. Looking through the central panels, I. sees Raven lying unconscious on a gaming table. He takes a huge typewriter from an office nearby, drops it through the glass and descends through the hole it has made into the gaming room; but Housemartin has taken Raven away and I. has to make a quick exit when the police raid the premises.

Dalby takes I. to Beirut where, in a bold and brutal ambush, they retrieve Raven; but in the process I. inadvertently kills two American agents. Back in London, a Scotland Yard acquaintance tips him off that a man posing as a police inspector is in custody at Shoreditch Police Station. I. hurries there only to find that Jay’s accomplices, posing as I.’s colleagues, have got there first. He finds the arrested man dead in his cell; it is Housemartin. I. learns from the policeman who arrested him that Housemartin may have come from a big secluded house that has recently undergone alteration. I. orders a raid on this house at 42 Acacia Drive, ‘a wide wet street in one of those districts where the suburbs creep stealthily in towards Central London’, but the house is empty.

As the quest for Jay seems to founder, Dalby invites I., and I.’s new and attractive assistant Jean Tonnesen, to go with him to the Pacific island of Tokwe Atoll to witness the test explosion of a neutron bomb. There, I. starts to realize he is suspected of being a double agent and he is arrested after allegedly being in contact with a Soviet surveillance submarine and killing a young US soldier by connecting a metal watch tower where he is on guard to a high tension power line. He is treated as a traitor and roughly interrogated by the Americans. He then finds himself in a prison which is, he is told, in Hungary. Here his rough physical and mental treatment is intensified.

I. does, however, succeed in getting back to London (it would be a spoiler for those who have not read the novel or seen the film to reveal how), and he does finally uncover a mass brainwashing network which relies on the ‘Induction of Psycho-neuroses by Conditioned Reflex with Stress’ – the basis of the word ‘Ipcress’. The destruction of this network provides a further revelation near the end of the book, which again we will not disclose here.

I. meets Jay and Housemartin in a Soho café called Lederer’s, ‘one of those continental-style coffee-houses where coffee comes in a glass’. Its customers, ‘who mostly think of themselves as clientele, are those smooth-rugged characters with sun-lamp complexions, half a dozen 10in by 8in glossies, an agent and more time than money on their hands’. Jay’s head touches ‘the red flocked wallpaper between the notice that told customers not to expect dairy cream in their pastries and the one that cautioned them against passing betting slips’. Today these details are redolent of a past era in which coffee in a glass was an exotic novelty, actors marketed themselves by means of glossy photographic prints rather than on the web, pastries were often filled with artificial cream, and there were no betting shops.

I. tells Jay he has a financial proposition for him, and Jay and Housemartin take him to what Jay says is a place where they can talk: the narrative offers a montage of I.’s visual impressions and jaundiced thoughts as they walk along Wardour Street:

the three of us trailed out along Wardour Street, Jay in the lead. The lunch hour in central London – the traffic was thick and most of the pedestrians the same. We walked past grim-faced soldiers in photo-shop windows. Stainless-steel orange squeezers and moron-manipulated pin-tables metronoming away the sunny afternoon in long thin slices of boredom. Through wonderlands of wireless entrails from the little edible condensers to gutted radar receivers for thirty-nine and six. On, shuffling past plastic chop suey, big-bellied naked girls and ‘Luncheon Vouchers Accepted’ notices, until we paused before a wide illustrated doorway – ‘Vicki from Montmarte’ [sic] and ‘Striptease in the Snow’ said the freshly-painted signs. ‘Danse de Desir – Non Stop Striptease Revue’ and the little yellow bulbs winked lecherously in the dusty sunlight.

Inside, left alone by Jay and Housemartin, I. decides to explore the premises by himself and finds an upstairs room whose floor is studded with six armour-glass panels, looking like mirrors from below, for covert observation of the gaming room beneath. Looking through the central panels, I. sees Raven lying unconscious on a gaming table. He takes a huge typewriter from an office nearby, drops it through the glass and descends through the hole it has made into the gaming room; but Housemartin has taken Raven away and I. has to make a quick exit when the police raid the premises.

Dalby takes I. to Beirut where, in a bold and brutal ambush, they retrieve Raven; but in the process I. inadvertently kills two American agents. Back in London, a Scotland Yard acquaintance tips him off that a man posing as a police inspector is in custody at Shoreditch Police Station. I. hurries there only to find that Jay’s accomplices, posing as I.’s colleagues, have got there first. He finds the arrested man dead in his cell; it is Housemartin. I. learns from the policeman who arrested him that Housemartin may have come from a big secluded house that has recently undergone alteration. I. orders a raid on this house at 42 Acacia Drive, ‘a wide wet street in one of those districts where the suburbs creep stealthily in towards Central London’, but the house is empty.

As the quest for Jay seems to founder, Dalby invites I., and I.’s new and attractive assistant Jean Tonnesen, to go with him to the Pacific island of Tokwe Atoll to witness the test explosion of a neutron bomb. There, I. starts to realize he is suspected of being a double agent and he is arrested after allegedly being in contact with a Soviet surveillance submarine and killing a young US soldier by connecting a metal watch tower where he is on guard to a high tension power line. He is treated as a traitor and roughly interrogated by the Americans. He then finds himself in a prison which is, he is told, in Hungary. Here his rough physical and mental treatment is intensified.

I. does, however, succeed in getting back to London (it would be a spoiler for those who have not read the novel or seen the film to reveal how), and he does finally uncover a mass brainwashing network which relies on the ‘Induction of Psycho-neuroses by Conditioned Reflex with Stress’ – the basis of the word ‘Ipcress’. The destruction of this network provides a further revelation near the end of the book, which again we will not disclose here.

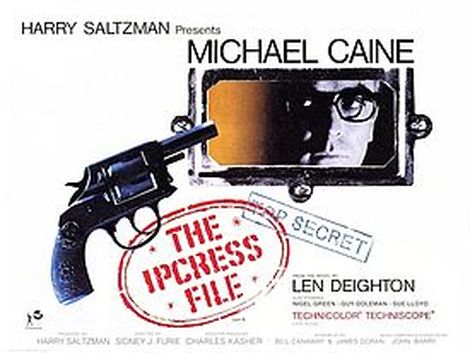

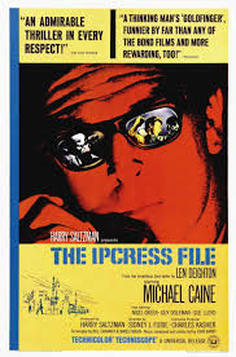

The film version of Ipcress (1965), directed by Sidney J. Furie, starred Michael Caine as its protagonist, who was called ‘Harry Palmer’. In the context of London fictions, its most notable difference from the novel is it has no excursions to Beirut or Tokwe Atoll. It is set almost wholly in London, apart from one brief scene supposedly on a French train and some scenes in a prison located, Palmer is told, in Albania. The film makes haunting use of London locations (the unofficial ‘Harry Palmer Movie Site’ provides an admirably detailed list, with photos, of these – see ‘References’ section below for link). But many of these locations differ from those in the novel.

For example, Palmer makes his first contact with Jay (codenamed Bluejay in the film), not in a Soho coffee-house, but in the old Science Museum library (which they actually enter through the door of the old Royal School of Mines, now part of Imperial College, in Prince Consort Road). In the library, Jay writes down a phone number for Palmer and tells him to ring that evening. Palmer goes to a phone box, specially put there for the film, on the steps behind the Albert Hall and dials the number to check it. The operator tells him the number is discontinued and at that point I. sees Bluejay and Housemartin climbing the steps. He hails them, Bluejay quickens his pace, and Housemartin turns to fight Palmer. The fight is seen through the panes of the phone box window, a grim dumbshow with music but no words. Housemartin finally runs back to Bluejay’s car and drives away.

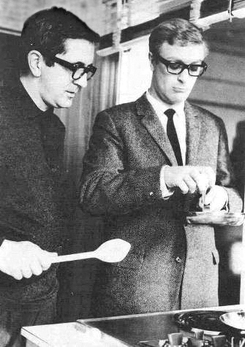

Len Deighton (l) with Michael Caine

Len Deighton (l) with Michael Caine

The shooting of the fight through the phone box window is one of the many optical idiosyncrasies and motifs in the film, admirably complemented by John Barry’s downbeat, intriguing score, very different from the pulsing excitement of his James Bond theme. Near its start, when Palmer wakes, we see, from his point of view, a blurred, unfocussed room that only sharpens into definition when he puts on his glasses.

In its earlier sequences, Palmer’s unknown tail is a man wearing glasses whose nose-piece is held together with sticking plaster – and our last sight of these glasses is on the floor of an underground car park, separated from their owner, after Palmer has acted on a fundamental misperception. The blank open eyes of a freshly-killed corpse punctuate the film, first in the pre-opening credit sequence and then just after Harry learns the meaning of ‘Ipcress’. There are many tilted camera angles and views from above and below.

These optical idiosyncrasies and motifs reinforce the sense that we are in a city, a microcosm perhaps of a nation and a world, where the true contours and proportions of people and things are difficult to discern clearly; where perception is blurred and off-balance; where the means of optical correction are fragile; and where only the eyes of the dead are open. In this respect, the film admirably complements and develops the mood of the novel. In its focus on London as the treacherous core of a diminished nation, it looks back to the ‘Unreal City’ of Eliot’s Waste Land and forward to the haunted metropolis, with its apparitions and absences, of Antonioni’s 1966 film, Blow-up.

Nicolas Tredell is a freelance writer. He is currently editor of Palgrave’s Essential Criticism series and formerly taught literature and film at Sussex University. His website is at http://nicolastredell.co.uk/

In its earlier sequences, Palmer’s unknown tail is a man wearing glasses whose nose-piece is held together with sticking plaster – and our last sight of these glasses is on the floor of an underground car park, separated from their owner, after Palmer has acted on a fundamental misperception. The blank open eyes of a freshly-killed corpse punctuate the film, first in the pre-opening credit sequence and then just after Harry learns the meaning of ‘Ipcress’. There are many tilted camera angles and views from above and below.

These optical idiosyncrasies and motifs reinforce the sense that we are in a city, a microcosm perhaps of a nation and a world, where the true contours and proportions of people and things are difficult to discern clearly; where perception is blurred and off-balance; where the means of optical correction are fragile; and where only the eyes of the dead are open. In this respect, the film admirably complements and develops the mood of the novel. In its focus on London as the treacherous core of a diminished nation, it looks back to the ‘Unreal City’ of Eliot’s Waste Land and forward to the haunted metropolis, with its apparitions and absences, of Antonioni’s 1966 film, Blow-up.

Nicolas Tredell is a freelance writer. He is currently editor of Palgrave’s Essential Criticism series and formerly taught literature and film at Sussex University. His website is at http://nicolastredell.co.uk/

References and further reading

Deighton, Len, The Ipcress File (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1962)

Deighton, Len, ‘Preface’ to The Ipcress File, Silver Jubilee edition (London: Grafton, 1987), pp. v-ix

Milward-Oliver, Edward, The Len Deighton Companion (London: Grafton, 1987)

Snyder, Robert Lance, The Art of Indirection in British Espionage Fiction: A Study of Six Novelists (Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland, 2011, esp. ‘The Ipcress File: Anonymity and Occultation’, pp. 90-7

Web sources:

The Deighton Dossier: http://www.deightondossier.net/index.html

The Harry Palmer Movie Site: http://keesstam.tripod.com/tifloc.html

Kerridge, Jake, ‘Interview with Len Deighton’, Telegraph, 18 Feb 2009:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/4681966/Interview-with-Len-Deighton.html

[Posted October 2013; minor reformatting August 2020]

All rights to the text remain with the author

And here's the link to the London Fictions home page

Deighton, Len, ‘Preface’ to The Ipcress File, Silver Jubilee edition (London: Grafton, 1987), pp. v-ix

Milward-Oliver, Edward, The Len Deighton Companion (London: Grafton, 1987)

Snyder, Robert Lance, The Art of Indirection in British Espionage Fiction: A Study of Six Novelists (Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland, 2011, esp. ‘The Ipcress File: Anonymity and Occultation’, pp. 90-7

Web sources:

The Deighton Dossier: http://www.deightondossier.net/index.html

The Harry Palmer Movie Site: http://keesstam.tripod.com/tifloc.html

Kerridge, Jake, ‘Interview with Len Deighton’, Telegraph, 18 Feb 2009:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/4681966/Interview-with-Len-Deighton.html

[Posted October 2013; minor reformatting August 2020]

All rights to the text remain with the author

And here's the link to the London Fictions home page