| London Fictions |

|

- Home

-

To 1900

- Daniel Defoe: A Journal of the Plague Year

- Charles Dickens: Great Expectations

- Walter Besant: All Sorts and Conditions of Men

- Amy Levy: Reuben Sachs

- Margaret Harkness: Out of Work

- Margaret Harkness: In Darkest London

- Julia Frankau: A Babe in Bohemia

- George Gissing: The Nether World

- Arthur Conan Doyle: The Sign of Four

- George Gissing: New Grub Street

- H.W. Nevinson: Neighbours of Ours

- Arthur Morrison: A Child of the Jago

- William Pett Ridge: Mord Em'ly

- M.P. Shiel: The Yellow Danger

- Arthur Morrison: To London Town

-

1901-1930

- Joseph Conrad: The Secret Agent

- A. Neil Lyons: Arthur's

- Thomas Burke: Limehouse Nights

- Dorothy Richardson: The Tunnel

- Virginia Woolf: Jacob's Room

- Arnold Bennett: Riceyman Steps

- Aldous Huxley: Antic Hay

- Virginia Woolf: Mrs Dalloway

- Christopher Isherwood: All the Conspirators

- Lao She: Mr Ma and Son

- Patrick Hamilton: The Midnight Bell

- Jean Rhys: After Leaving Mr Mackenzie

- A.P. Herbert: The Water Gipsies

-

1931-1960

- Pamela Hansford Johnson: This Bed Thy Centre

- Simon Blumenfeld: Jew Boy

- John Sommerfield: May Day

- James Curtis: The Gilt Kid

- Virginia Woolf: The Years

- Samuel Beckett: Murphy

- Sajjad Zaheer: A Night in London

- John Sommerfield: Trouble in Porter Street

- Patrick Hamilton: Hangover Square

- Graham Greene: The Ministry of Fear

- Louis-Ferdinand Celine: Guignol's Band I & II

- Norman Collins: London Belongs to Me

- Elizabeth Bowen: The Heat of the Day

- George Orwell: Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Rose Macaulay: The World My Wilderness

- Graham Greene: The End of the Affair

- Alexander Baron: Rosie Hogarth

- Jack Lindsay: Rising Tide

- Iris Murdoch: Under the Net

- Samuel Selvon: The Lonely Londoners

- Gerald Kersh: Fowlers End

- Colin MacInnes: City of Spades

- Kevin FitzGerald: Trouble in West Two

- Colin MacInnes: Absolute Beginners

- E.R. Braithwaite: To Sir, with Love

- Lynne Reid Banks: The L-Shaped Room

- Colin MacInnes: Mr Love and Justice

- Colin Wilson: Ritual in the Dark

-

1961-1990

- Colin Wilson: Adrift in Soho

- Terry Taylor: Baron's Court, All Change

- Laura Del-Rivo: The Furnished Room

- Robert Poole: London E1

- Len Deighton: The Ipcress File

- Alexander Baron: The Lowlife

- B.S. Johnson: Albert Angelo

- Waguih Ghali: Beer in the Snooker Club

- Anthony Cronin: The Life of Riley

- Nell Dunn: Poor Cow

- Kamala Markandaya: The Nowhere Man

- Lionel Davidson: The Chelsea Murders

- Penelope Fitzgerald: Offshore

- J.M. O'Neill: Duffy is Dead

- Muriel Spark: A Far Cry from Kensington

- Martin Amis: London Fields

- Hanif Kureishi: The Buddha of Suburbia

- Neil Bartlett: Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall

- Nigel Williams: The Wimbledon Poisoner

-

1991 on

- Peter Ackroyd: The Plato Papers

- Zadie Smith: White Teeth

- Chris Petit: The Hard Shoulder

- Iain Banks: Dead Air

- Monica Ali: Brick Lane

- Naomi Alderman: Disobedience

- Xiaolu Guo: A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers

- Jonathan Kemp: London Triptych

- Martin Amis: Lionel Asbo

- Zadie Smith: NW

- Paula Hawkins: The Girl on the Train

- Natasha Pulley: The Watchmaker of Filigree Street

- Kamila Shamsie: Home Fire

- Michele Roberts: The Walworth Beauty

- Balli Kaur Jaswal: Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows

- Claire North: 84K

- Tony White: The Fountain in the Forest

- Vesna Goldsworthy: Monsieur Ka

- Contact

Vesna Goldsworthy: 'Monsieur Ka' - 2018

=Jane McChrystal=

What happens to people caught up in the chaos of revolution and war, when their lives have already been riven by displacement and loss? What distinguishes those who break from the survivors? Monsieur Ka, Vesna Goldsworthy’s second novel, is a sensitive, perceptive exploration of these questions.

Goldsworthy based Monsieur Ka on the premise that Tolstoy modelled his Anna Karenina on a real woman, with a real son who grows up to become her eponymous hero. The novel charts his progression through the Russian Revolution and the First and Second World Wars, from bereaved child to elderly exile in a South West London suburb, where he has assumed the semi-anglicised identity of Mr Carr. With old age and increasing infirmity, he becomes bored and isolated, so his son, Alex, decides to engage a young Jewish woman, Albertine, for a few hours a week to read and converse with him in her mother tongue, French. A genuine affection grows between them during their meetings and Monsieur Ka tells Albertine the story of his life which she writes up in a memoir, “The Winter of Mr Karenin”.

The novel is narrated mainly from the viewpoint of Albertine Whitelaw, who finds herself stranded in London two years after the Second World War, with a husband who is frequently absent and little to occupy her while he is away. The duties she performs for Monsieur Ka provide her with the means to fill some of the empty hours, along with the chance to build a new friendship.

The novel is narrated mainly from the viewpoint of Albertine Whitelaw, who finds herself stranded in London two years after the Second World War, with a husband who is frequently absent and little to occupy her while he is away. The duties she performs for Monsieur Ka provide her with the means to fill some of the empty hours, along with the chance to build a new friendship.

Monsieur Ka’s Story is framed within Albertine’s recollections of her husband, Albert Whitelaw, an army officer whose work involves frequent trips to Berlin, Geneva and Paris, where he is part of the British government’s mission to sort out the devastation left behind by the war in Europe.

The theme of parental loss is woven into the narrative, starting with Anna Karenina’s suicide, then Albert’s exile from India to boarding school in England as a small boy and the death of Albertine’s mother, father and sister in a train crash outside Paris in 1933. The past hurts the couple share do not bring them closer together, rather they become part of a barrier which cannot be breached and is reinforced by the profound differences in their backgrounds. A passionate attachment for one another is not enough:

Our marriage stood beneath a dam of unacknowledged matter. A levee of sandbags against the flood; we seemed unsure what we feared, what more could have burst in.

The novel opens during the coldest winter in Britain since 1814. The mains freeze and Londoners queue in the streets for water dispensed from enormous canisters. Albertine passes them on the way to her first meeting with Monsieur Ka, the day after an ice storm has passed over London in the night:

The following afternoon, the streets looked shiny, as though everything on them had been sheathed in glass. Branches glistened darkly, clinking as they swayed. The tips of my fingers, my ear lobes and the flares of my nostrils tingled. The chill stung every inch of exposed skin the moment I stepped off the train. By the time I had left the station and crossed the road, my hands felt as dead as the branches.

Physical comfort is hard to find in her Earls Court home, which is impossible to heat and where regular power cuts leave her with no electric light for hours at a time. A fuel crisis, exacerbated by strict austerity measures imposed by the Ministry for Fuel and Power, inflicts further privation on Londoners, who also have to queue for rationed food, aware that they were the ones who were supposed to have emerged victorious from the war.

Much of London lies in ruins, which hold fast the memories of those who perished in the minds of those who witnessed the destruction. Albert cannot forget a young woman he helped dig from the rubble and the way the pencil line, drawn on her leg in imitation of a seamed stocking, smudged as they pulled her out. His recollection shatters an anniversary celebration in the West End, as the couple pass by Air Street near the site of the bombing and Albertine considers how close he came to losing his life on the night of the raid.

In the afterword to Monsieur Ka Goldsworthy acknowledges the pleasure she took in her research into conditions found in the London of 1947, which she has applied with a light touch to evoke to a city wrecked by war, in the grip of a seemingly endless freeze. The enjoyment taken in her writing is plain to see throughout the novel which, despite its sombre themes, never descends into a misery-fest.

Although Albertine feels aimless and adrift in her adopted land, she is still open to the pleasures of domesticity and delights peculiar to London with all its squares and wide-open spaces. She cooks delicious meals redolent of home from the measly food rations and sews her own designs for clothes, using skills passed down by generations of Parisian tailors in her family. She learns Russian as a surprise for Monsieur Ka and draws satisfaction from her growing competence as a biographer:

Whenever I returned home from Chiswick, I typed new sections of Monsieur Carr’s memoir on separate sheets of paper. I noted his life’s events in the order in which he told them, giving each sheet a heading with the place and the period he described as close as I could guess them … The gaps in chronology were still vast, but many episodes from Monsieur Carr’s life were coalescing into the chapters of a future volume.

During the hours she spends wandering the streets of London she catches glimpses of family life: wives welcome their husbands home from work into houses filled with the sounds of children, pets and music on the radio. She wonders whether her marriage will ever be ordinary like this.

Chiswick forms the backdrop to much of the novel, where Monsieur Ka lives in Bedford Park, England’s first garden suburb, and as she gets to know him, Albertine learns the stories of other White Russians who have set up home there. It’s no wonder these emigres gravitated to this estate of Queen Anne revival style houses with its perpendicular gothic church and tennis courts. Bedford Park must have looked like the epitome of orderly, middle-class life to people desperate for stability after the cataclysms of war and revolution.

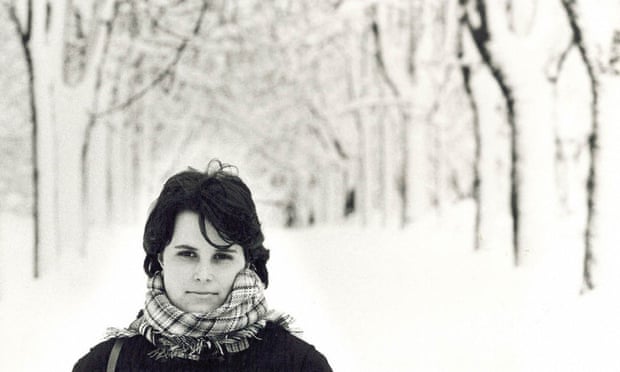

Goldsworthy herself is a Serbian national who arrived in England in 1986, where she worked as an academic, writer and broadcaster for the BBC World Service. She moved to Chiswick in 1988 and was surprised to find a substantial community of elderly Russians there who had established their own care home, and marked their presence in the local cemetery with the distinctive Orthodox three bar cross. It’s more than likely that the stories they told her formed the templates for their fictional counterparts.

The theme of parental loss is woven into the narrative, starting with Anna Karenina’s suicide, then Albert’s exile from India to boarding school in England as a small boy and the death of Albertine’s mother, father and sister in a train crash outside Paris in 1933. The past hurts the couple share do not bring them closer together, rather they become part of a barrier which cannot be breached and is reinforced by the profound differences in their backgrounds. A passionate attachment for one another is not enough:

Our marriage stood beneath a dam of unacknowledged matter. A levee of sandbags against the flood; we seemed unsure what we feared, what more could have burst in.

The novel opens during the coldest winter in Britain since 1814. The mains freeze and Londoners queue in the streets for water dispensed from enormous canisters. Albertine passes them on the way to her first meeting with Monsieur Ka, the day after an ice storm has passed over London in the night:

The following afternoon, the streets looked shiny, as though everything on them had been sheathed in glass. Branches glistened darkly, clinking as they swayed. The tips of my fingers, my ear lobes and the flares of my nostrils tingled. The chill stung every inch of exposed skin the moment I stepped off the train. By the time I had left the station and crossed the road, my hands felt as dead as the branches.

Physical comfort is hard to find in her Earls Court home, which is impossible to heat and where regular power cuts leave her with no electric light for hours at a time. A fuel crisis, exacerbated by strict austerity measures imposed by the Ministry for Fuel and Power, inflicts further privation on Londoners, who also have to queue for rationed food, aware that they were the ones who were supposed to have emerged victorious from the war.

Much of London lies in ruins, which hold fast the memories of those who perished in the minds of those who witnessed the destruction. Albert cannot forget a young woman he helped dig from the rubble and the way the pencil line, drawn on her leg in imitation of a seamed stocking, smudged as they pulled her out. His recollection shatters an anniversary celebration in the West End, as the couple pass by Air Street near the site of the bombing and Albertine considers how close he came to losing his life on the night of the raid.

In the afterword to Monsieur Ka Goldsworthy acknowledges the pleasure she took in her research into conditions found in the London of 1947, which she has applied with a light touch to evoke to a city wrecked by war, in the grip of a seemingly endless freeze. The enjoyment taken in her writing is plain to see throughout the novel which, despite its sombre themes, never descends into a misery-fest.

Although Albertine feels aimless and adrift in her adopted land, she is still open to the pleasures of domesticity and delights peculiar to London with all its squares and wide-open spaces. She cooks delicious meals redolent of home from the measly food rations and sews her own designs for clothes, using skills passed down by generations of Parisian tailors in her family. She learns Russian as a surprise for Monsieur Ka and draws satisfaction from her growing competence as a biographer:

Whenever I returned home from Chiswick, I typed new sections of Monsieur Carr’s memoir on separate sheets of paper. I noted his life’s events in the order in which he told them, giving each sheet a heading with the place and the period he described as close as I could guess them … The gaps in chronology were still vast, but many episodes from Monsieur Carr’s life were coalescing into the chapters of a future volume.

During the hours she spends wandering the streets of London she catches glimpses of family life: wives welcome their husbands home from work into houses filled with the sounds of children, pets and music on the radio. She wonders whether her marriage will ever be ordinary like this.

Chiswick forms the backdrop to much of the novel, where Monsieur Ka lives in Bedford Park, England’s first garden suburb, and as she gets to know him, Albertine learns the stories of other White Russians who have set up home there. It’s no wonder these emigres gravitated to this estate of Queen Anne revival style houses with its perpendicular gothic church and tennis courts. Bedford Park must have looked like the epitome of orderly, middle-class life to people desperate for stability after the cataclysms of war and revolution.

Goldsworthy herself is a Serbian national who arrived in England in 1986, where she worked as an academic, writer and broadcaster for the BBC World Service. She moved to Chiswick in 1988 and was surprised to find a substantial community of elderly Russians there who had established their own care home, and marked their presence in the local cemetery with the distinctive Orthodox three bar cross. It’s more than likely that the stories they told her formed the templates for their fictional counterparts.

Goldsworthy’s portrayal of her London setting can be sketchy, so when she conjures up a location in greater detail, the images created are all the more arresting. Here is Albertine visiting the site of Alex Carr’s brewery in Twickenham:

I found myself in the vast office on the first floor of a Georgian terrace with bricks the colour of congealed blood and rows of black-framed windows reflecting the snow. The street sloped towards the Thames like a slide. There were the beginnings of an island at the bottom – an eyot …

Anyone familiar with the area will be able to picture the identical terrace on Chiswick Lane South, just as the City pub with its reliefs of jolly monks, satyrs and gargoyles can only be the Black Friar on Queen Victoria Street. A memory of people painted on the cupola of the Wigmore Hall reaching out through a tangle of thorns towards Harmony, seen as a golden sphere, has a powerful effect on Albertine as she envisages people from her past and present passing before her, the most poignant of which is:

… Albie’s face, his hair oiled and carefully combed yet falling in strands above me; all of us striving for that golden sphere; Albie again on this same bed twenty-four hours ago, getting closer, moving away, falling towards me, moving away.

In the same way as the painting induces a kind of meditative state in Albertine, so London, under its cape of snow, becomes a projection screen for the memories and hopes of thousands of people swept here by the war, summed up in the words of Alex as he stands with Albertine in the grounds of Chiswick House:

“Isn’t it beautiful here?” he asked. “Have you noticed that chameleon quality in London, how it turns into any European city you’d like it to be? Suddenly you are in Rome, or in Paris, or in Vienna or God Forbid, even in Berlin. Suddenly you are at home”.

I have tried to give some idea of the riches Goldsworthy packs into a novel of fewer than three hundred pages but there is much more for the reader to discover: literary allusions to memory and adultery abound; stories are enfolded within stories which reflect each other’s themes; the narrative travels between Nineteenth Century Russia to Twentieth Century post-war London stopping off at many points along the way; the point of view from which it’s told switches between Albertine and Monsieur Ka, but Goldsworthy is always firmly in charge of her narrative, so the reader always knows exactly where they are, and this complexity is part of what makes it such a compelling read.

Then, there is Goldsworthy’s prose - pared down and precise but still lyrical, with different voices, from elderly Russian Aristocrat to laconic British army officer, perfectly rendered, a remarkable achievement when you consider English is her third language.

Goldsworthy’s characters are called on to reconcile a history of personal damage with the struggle to find a way to be in a world they could never have imagined. Some don’t survive, others carry on, but just get by with an essential part of the self missing. But there is still hope -anybody who has been held properly by another at critical moments in life can go on to live fully and pass the blessing on. As Albertine writes on the final page of Monsieur Ka:

I needed to have someone to hold me when it was all over. Someone to hold me so that I could hold you.

Jane McChrystal is an independent researcher and writer based on the Isle of Dogs. She writes about a wide variety of European cultural and historical subjects - https://londongrip.co.uk/tag/jane-mcchrystal/ - with a particular interest in the history of the East End of London, especially the women of the East London Federation of Suffragettes.

[Posted November 2019; minor reformatting August 2020]

All rights to the text remain with the author

And here's the link to the London Fictions home page